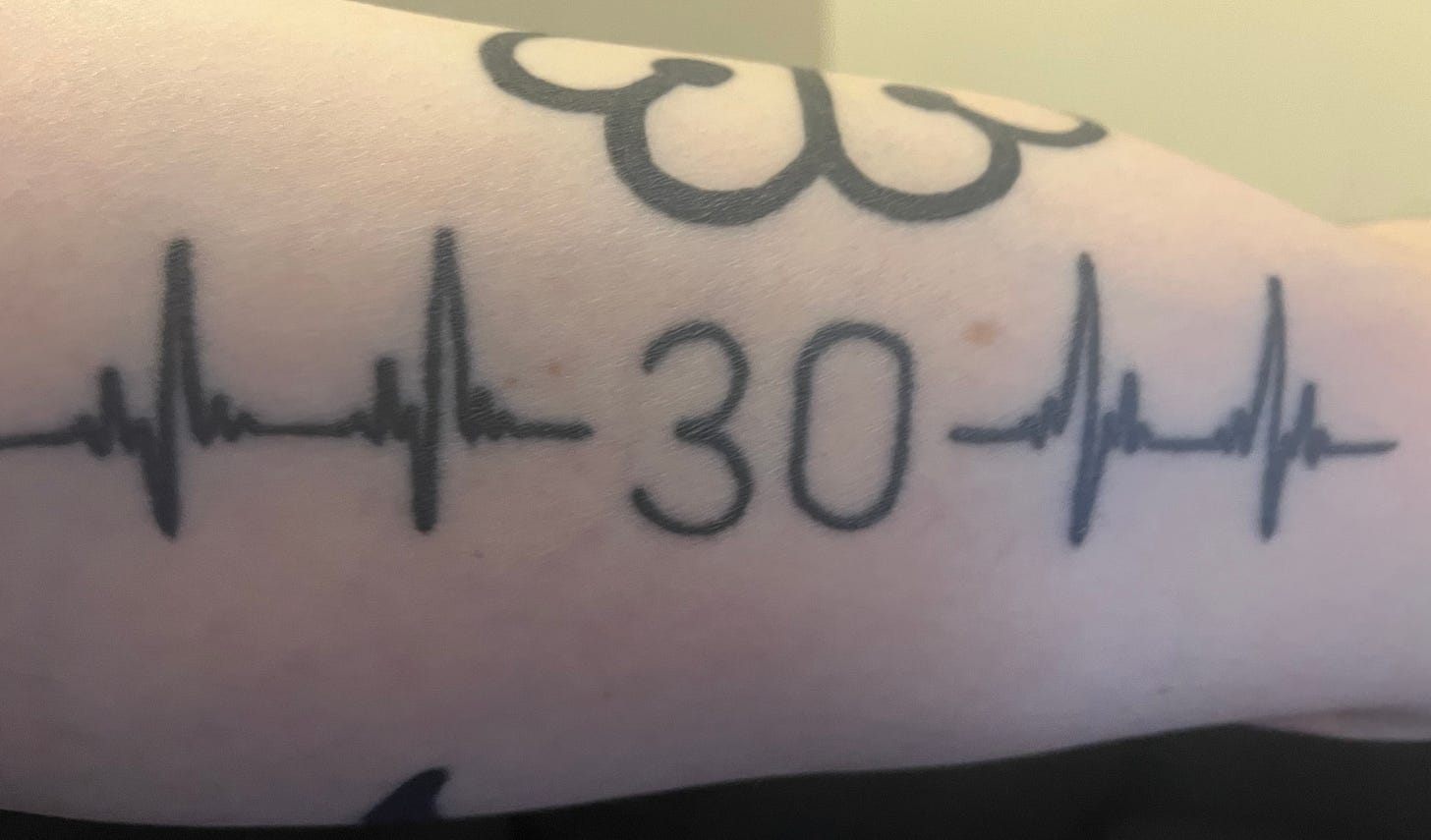

You might be wondering about the tattoo.

This site’s logo was chosen for two reasons. The first is that I don’t know how to create digital art and have a philosophical queasiness about using AI to generate images. The second is that the tattoo commemorates the worst day of my life, but also every single day that followed.

In journalism, the symbol -30- is meant to convey the end of an article. It’s not often used anymore; it’s one of those anachronisms that we all still fondly think of, like the term “ink stained wretches,” but that doesn’t really work in a modern context. It’s a leftover from the ages when pages were slowly sent by teletype by reporters out in the field, long before the invention of smartphones and email. Its origin is a mystery.

On June 27, 2020, a few months into the global pandemic, I suffered a near-fatal heart attack at the age of 35. For a while, I remained convinced I was supposed to die that day, that it was meant to be my own -30-. I survived. I avoided that permanent flatline, my article’s ending had not yet been written.

Below is an essay I wrote a few years ago as an assignment for my master’s degree. I pitched it around, but personal essays are not really my territory and I never did quite figure out what publications it would fit. So it’s sat in a Google drive and in the back of my mind.

One of the regular features of this Substack will be interviews with people who came close to dying. I’m still trying to make sense of what happened to me and the thinking is, maybe by talking to others who have gone through the same, I can find a bit of enlightenment, possibly even some catharsis. Maybe it will just make death a little bit less scary for those who find this site. This essay is likely to be the last time I write about myself, as my life is a topic I find deeply uninteresting, at least compared to everything else in the world there is to explore. But if I’m going to ask others to share their stories, it’s only fair I share mine first.

Blood goes where it must. Given options, it would go anywhere, but we confine it to the winding tunnels of veins and arteries and capillaries. We keep it prisoner, forcing it to do the hard work of keeping our cells up and running. Blood goes where it must, until given a chance to jailbreak. Then blood goes where it can.

I know this because of the crimson splashes I spied on the surgical sheet to my right. The surgeon had been rooting around in my wrist, snaking his tiny instruments through the artery to the blood clot in my heart.

Blood goes where it must, until it can’t. Sometimes it holds a prison riot and everything collapses. The incarcerated, for whatever reason, have had enough. They gather together, they form a clot, they will not let anyone pass as they hold their silent protest. The doctors call this a myocardial infarction. When the blockage forms in the left anterior descending artery specifically, they call it a widowmaker. The irony of that term will be apparent in a minute.

I call it the Incident, or the Thing That Happened, or, if I’m feeling playful, the Time My Heart Went Kablooey. Never the heart attack.

The doctor and his tiny instruments really got to the heart of the matter, you could say.

Very little of this is clear in my mind. Two microdoses of fentanyl have a way of making things fuzzy. But I remember, after they applied the bandage to my leaking wrist with a clamp, there was a heated blanket laid on my chest. It felt like a warm hug. And then I was wheeled to my recovery room to start my life again.

When I was put in the ambulance, I had been wearing nothing but a pair of boxers, a t-shirt and my glasses. Despite the agony, I had the foresight to bring my phone. There was the pain and the terror. The terror of my body turning on me and that my last chance to tell people I loved them would be by FaceTime.

A pandemic isn’t a great time for an Incident. Visitors are not allowed, not even to the cardiac intensive care unit. Canadian healthcare is free; the television sets in recovery rooms are not. I remembered my phone; I did not remember my credit card. There is plenty of time to nap and to wake up and wonder when you started screwing up, how you end up in a place of literal heartbreak.

Maybe it’s fate. Maybe we all go where we must.

When I was in elementary school, sometimes I would get sick. There was a protocol; people knew what to do. My parents would get called; they’d come to school and load me up and bring me home to plop me on the couch. My mom had one of those old strip thermometers, you put it against a clammy forehead. She would press it down and interpret it by some magic that my young mind couldn’t comprehend.

Sometimes, it wasn’t needed. Sometimes, she’d just kiss my forehead. “You feel warm,” she’d declare and she’d make sure my blanket was snuggly enough. “You’re going to be okay in a day or two,” she’d add, words coated in the loving confidence I assumed all Grown Ups had an endless reservoir of.

My blood vessels were expanding and contracting, battling the evil invaders by raising the internal thermostat. Once I was old enough to know some basic biology, I imagined white blood cells, sporting medieval armor and lances, charging onto a battle field too small to see, the cavalry supported by their allies Hot Tea and Plain Toast. Even before that, at an age where I was barely literate, I had a vague notion that the precious juices were all going where they needed to go to make me better. I couldn’t care less back then; all that mattered was that magical elixirs like Tylenol were administered by a loving hand.

There is no protocol for a 35-year-old man having a heart attack. It’s so rare that the paramedics and doctors repeatedly quizzed me on how much cocaine I had been doing. Statistically, it made more sense for me to be doing lines in bed at 10 a.m. on a Saturday than for This Thing to Happen.

The normal illness platitudes kinda go out the window at that point. “You’re going to be okay” is weightless, the words turn to vapor before they even make it to the air. But you long to hear them anyway, on the off chance they can transmogrify into matter.

The first call from the hospital bed was to my partner in a marriage that had been dissolving so long it was hanging like wet tissue. “I love you so much!” she had screamed at the closing ambulance doors.

Four days later, she asked for a divorce. There were many reasons, the little resentments that pile up over time, tiny trickles of water running down an ice shelf until, finally, it collapses into the sea. That final drop, she explained, was me crying harder upon my release into the wild at seeing my father and brother than when seeing her.

I told you widowmaker was ironic.

The next call was to my parents. I could see them fighting back tears on the tiny Gorilla Glass screen. “You’re going to be okay,” they said. Their voices still had that loving confidence, unevaporated despite the decades that had passed. With my own reservoir depleted, I chose to believe them.

For two days, the doctors came by the bed. Dietitians, with lists of the acceptable and unacceptable foods for the rest of my life. Cardiologists, explaining the wonderful pills that would ensure my continued survival. Some for cholesterol and some to thin my blood, some to control its pressure. Blood goes where it must but sometimes you need to make its paths more orderly.

None of them hugged me. None of them checked my blankets. None of them talked about failing marital unions or rebuilding your life or survivor’s guilt or depression.

They make you well enough to keep living, but nobody tells you why you should.

They send you back out into the world and maybe you can feel a hug, a real one, and someone tells you they were scared and that you are loved.

Blood goes where it must and sometimes we call it home.

Fabulous writing Adam!